Liberalism and Decline

A denomination's level of orthodoxy explains much of the variation in its growth/decline in membership over the past several decades.

There is this idea among academic theologians and the sociologists who study them that theological liberalization—watering down of faith, abandoning core tenets of the Christian faith along the way, to meet people where they are in the increasingly rational and skeptical cultures that they live in—is inevitable.

The cultural tides are against orthodoxy, so sayeth the sociologists of religion steeped in theories of secularization. Modernity and science undermine metaphysical thinking, focusing moderns’ thinking on what really matters: matter, in the here and now. Democracy and egalitarianism undermine hierarchy, especially the hierarchy inherent in divine revelation and any priesthood entrusted with it. Cultural diversity requires that people abandon strongly-held convictions in favor of a live-and-let-live-mode of acceptance—and privatize any religious practices in order to keep the peace, just in case someone misunderstands.

Many pastors have internalized this story in ways that are reflected in their practice—though often in their words, too. So the argument goes, churches need to be seeker sensitive if they are to attract and retain the modern man or woman. They need to appear less judgmental, by which people mean less insistent on adhering to core beliefs and practices—let alone preaching these. Epistemic humility must be extended to the point that pastors cannot insist they have any lock on the truth, acknowledging that theirs is merely one of many viewpoints on questions about the here-and-now and hereafter, and maybe they are entirely wrong on the matter—or maybe even that there is no right or wrong answer to be found.

All of this waters down the orthodoxy that churches used to insist upon, yes, but the pastors and theologians who think they are well clued in to the forces moving history insist that such is necessary to reach those outside the faith. What message they share with them becomes more difficult to articulate in a context in which the truth becomes increasingly diluted. Yet this makes de-emphasizing orthodoxy all the more important so that those outside the church can be reached with whatever message remains to be told now before it has to be diluted even further in the future.

If you’re anything like me, you’re skeptical of such circular (round and round the drain) thinking. I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again and again: liberalizing theology undermines religion. If pastors have no conviction in what they preach—or worse yet, if they stop preaching convictions altogether and devolve into contentless motivational speaking—why should those who they are trying to reach? If anything, a lack of conviction and commitment sends a signal that a church’s teachings are obviously untrue, and thus not to be taken seriously—and if that’s the case, what’s the point in such a religion? Or in religion at all if that’s all that is on offer?

All this leads to the conclusion: contrary to the academic theologians, sociologists of religion, and pastors imbibing their work who say that liberalizing theology is necessary to spread and save the faith, liberalization merely undercuts it. Rather than attracting new members—or at least stopping the hemorrhaging of members—liberal theology accelerates the decline.

A stark example illustrating these points came to me recently as I explored an old survey conducted in 1963 by two big names in the sociology of religion (one of whom, Stark, started as a devotee of the secularization story but later “converted” to become one of its fiercest critics). The survey had a fairly large sample size (nearly 3000 interviews), which allowed me to break the results down for several denominations and report the results with a good deal of (statistical) confidence. Although the survey was conducted among people living in the Bay Area of California, the fact that it was representative allows us to generalize to at least that part of Northern California; as we will see, there is a good evidence that these responses allow us to generalize to those denominations covered by the survey on a national scale.

What attracted me to the survey was the large battery of questions dealing with questions of theology. Who was/is Jesus? Was He born of the Virgin Mary? Is He our savior, and is belief necessary for salvation? Did He actually walk on water? Are Heaven and Hell real?

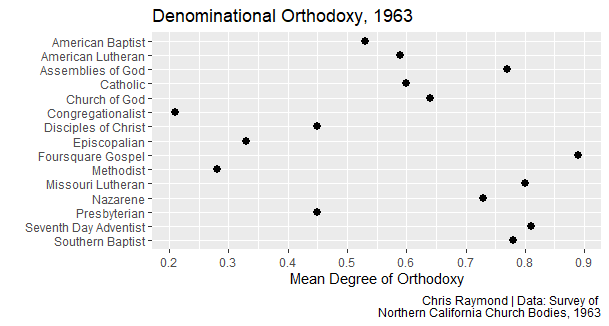

Combining the responses to 11 questions on matters of standard, orthodox Christian theology, I was able to construct a scale measuring respondents’ degree of orthodoxy (re-scaled to range from 0, no orthodox Christian beliefs, to 1, having orthodox views on all 11 items included in the scale). Using this scale, I was able to construct an average degree of orthodoxy for 15 Christian denominations.

Although this survey was conducted only among residents in the greater Bay Area, the levels of orthodoxy captured for the denominations with sufficient numbers of respondents to generate an average more than pass the gut test. Southern Baptists, Seventh Day Adventists, those belonging to the Assemblies of God, members of the Foursquare Gospel church, and the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod stand out as the most orthodox. Episcopalians, Methodists, and Congregationalists round out the bottom. However limited the geographic focus of the survey, the orthodoxy of the average respondent in each denomination matches what one would expect to observe if the survey had been conducted nationally.

The first takeaway from this exercise was to see that the patterns in theological liberalization among the major denominations in the United States today were very much evident 60 years ago. The most liberal churches today, some venturing well into heresy, were already on a clear liberal path long ago. Those denominations that stand out today as conservative holdouts do so because they have, well, held onto theological orthodoxy over the past 60 years (more than that if you make the easy assumption that these denominations were orthodox believers in the past). While this does not allow us to evaluate the degree to which denominations have held firm or liberalized over the past 60 years, this survey illustrates quite well the general trajectories that each denomination has taken: the liberals today were evidently liberalized or liberalizing several decades ago, perhaps ahead of the curve on accepting their supposedly inevitable liberal future.

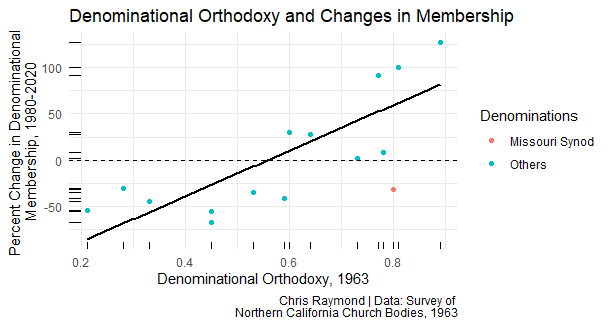

The second takeaway is that orthodoxy, or the lack thereof, maps well onto the fate of these denominations. Using changes in denominational membership between 1980 and 2020 taken from the US Religion Censuses of those years, we see that those denominations with the most theologically liberal congregations in the 1960s experienced significant losses in membership in the decades that followed. Not declines in the percentages of Americans belonging to these churches. Not barely keeping pace with increases in population. Absolute declines in church membership, of more than 50 percent in the most liberal denominations.

The denominations that have managed to hold on against the tide of secularization that has swept the country over the past half century, or in some cases even to grow in the face of such headwinds, are those that were the most orthodox. The Assemblies of God grew by nearly 92 percent. The Seventh Day Adventists doubled in size between 1980 and 2020. The Foursquare Gospel grew by 127 percent. Here, the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod stands out among the most orthodox denominations because it experienced membership decline—though this is due largely to the fact that the liberal factions within the church split off in 1976. This would appear to be a case of the exception proving the rule.

All this is to say that I am skeptical when I hear that the faith must be reduced so that it must be increased. Several denominations, especially of the mainline that once dominated the religious landscape of the English-speaking world, followed the advice that they received from the learned and adopted liberal theology—or did away with an attempt to appear to adhere to orthodoxy at all—and all it did was ruin them. While the growth observed among the most orthodox denominations pales in comparison to the total loss of believers experienced by the mainline, putting faith in a liberalized Christianity (to the extent that it can be called Christian) is to condemn it to the past.