Rich in Income, Poor in Attendance?

Sociologists insist that wealth undermines religiosity, but the evidence shows this need not, and has not, always been the case

One of the few points where theory developed by secular sociologists seems to align with the teachings of Christ is that wealth and religion are at odds with one another. Sociologists of religion hold that the material security that comes with wealth reduces the need for religion to cope with the stresses of life. Jesus put it more succinctly—and more starkly—when he said “It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God.”

The conventional wisdom is that religiosity—rates of church attendance, frequency of prayer, etc.—decline with income. This is supported by several studies showing that those with higher incomes tend to practice their faith less often than those with lower incomes. Moreover, such a pattern fits with the broader macro-sociological trends that wealthier, more materially secure countries tend, on the whole, to be less religious than poorer countries, and that as countries become wealthier, their populations tend to become less religious.

Jesus and the the rich man as the latter learns just how difficult it will be for him to get into Heaven given his current material state.

And yet the relationship between income and religiosity is not as open-and-shut a case as it may seem at first glance. While the Christian left has always referred to this passage in Scripture to condemn the wealthy, and while it is a message that haunts all Christians who hear and reflect on it, the early Church held that Jesus’ message was more nuanced than what it seems on first reading. As Clement of Alexandria taught,

“If you know how to use it [wealth] well, it will bring you justice; if you use it badly, it will reveal the injustice that is in you. By its very nature it is made to serve, not to command. Wealth, in itself, is neither good nor bad; it does not bear responsibility and therefore does not bear guilt. It is up to the human will, to his ability to choose, to establish how to use the wealth he possesses. It is absurd, therefore, to reject wealth rather than the passions of the soul. In this case, it becomes impossible to make the best use of external goods together with the achievement of inner perfection.”

In keeping with such a view, the Church has always offered the wealthy opportunities to give of themselves so that they are not consumed by their wealth like the rich man Jesus warned. Those of means have always been encouraged to steward their resources for the good of the Church, not only to aid the construction and maintenance of Cathedrals and schools, but to provide for the poor.

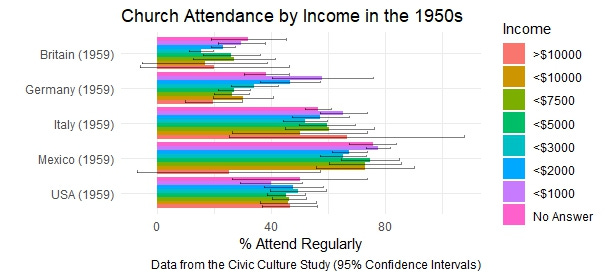

Not only did the early Church teach that wealth in and of itself is not evil, but the empirical relationship between wealth and religiosity has not always been as clear-cut as secular sociologists of religion would have us believe. Consider this evidence from a survey of five countries in the late 1950s: although income distributions varied significantly, household income was measured on the same scale in each country. This permits us to examine the relationship between income and church attendance across several cases in a way that is not dependent on context.

What is most remarkable about these patterns is how unremarkable the relationship between income and regular church attendance is. The relationship between income and regular church attendance is flat in the United States—and with the exception of the wealthiest band where there are very few respondents, in Mexico, too. The relationship is flat in Italy as well, though it is interesting that the wealthiest income group is the one most likely to attend regularly (however noisy that particular estimate may be).

It is only in Britain and Germany where we see a negative association between income and church attendance. This relationship is hardly convincing in Britain, where the sample variability at higher income levels is so great that we cannot tell whether the lower rates of church attendance among the wealthiest are genuine or a luck of the draw with this particular sample. It is only in Germany, then, that we see what seems like a clear negative relationship between income and church attendance.

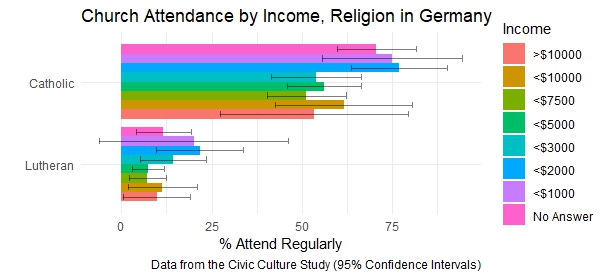

And yet, the relationship between income and church attendance seen at first blush in Germany is not what it seems. Because German Catholics (1) attended church services more frequently than Protestants, and (2) were under-represented at the higher end of the income distribution—and over-represented at the lower end of the income distribution—what appears like a negative relationship between income and church attendance in the figure above may actually be due to the composition of the sample.

This is in fact what we see when we break the relationship between church attendance and income down by religion. There is some evidence that those with the lowest incomes attend more frequently than those with middle and higher incomes. Due to sampling variability, however, no clear-cut relationship between income and church attendance appears for either Catholics or Protestants. So great is the variability that we cannot even be confident that those with the highest incomes attend less frequently than those with the lowest incomes (this is especially the case with Lutherans).

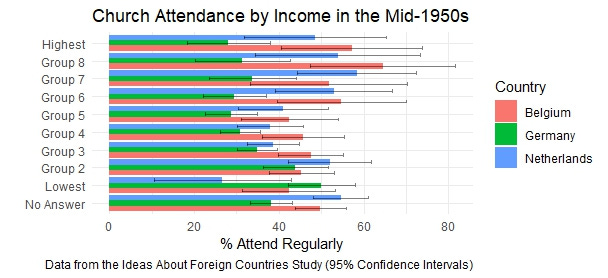

There may be some whose first reaction is to dismiss these findings as merely the result of one survey that just happened to produce an unrepresentative sample—though doing so five times, in each of the five countries sampled. Such skepticism is unsupported, however, as another set of surveys conducted in 1956 confirms the patterns—or the lack of any discernable pattern—seen above.

Again, it is only Germany that stands out as having anything resembling a negative association between income and church attendance. In Belgium, church attendance tends to increase as one moves from low- to high-income bands. Although there is too much sample variability in the higher-income buckets with the fewest respondents to say that wealthier respondents were more likely to attend regularly than low-income respondents, the differences between high- and middle-income buckets are significantly different.

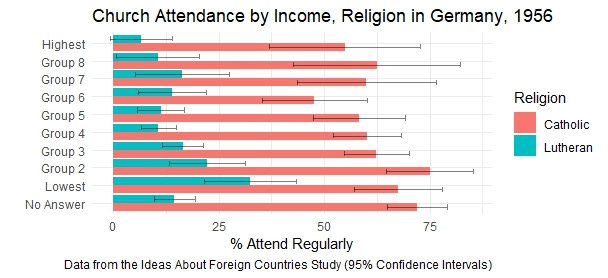

As with the data collected later in the decade, there is little evidence of a relationship between income and Mass attendance among German Catholics in the data from 1956. Among Lutherans, there is some evidence that church attendance declines with income, at least when comparing those in the lowest income band with those in the highest. That said, looking across the entire income distribution, the relationship is less than compelling, not only because church attendance is low across the board, but also because rates of church attendance among groups 3 through 8 are statistically indistinguishable from one another.

Do the rich have a harder time keeping the faith than the poor, who are utterly dependent on God for their survival? One can certainly imagine that would be the case, especially in an increasingly secular, and wealth-obsessed culture. But that doesn’t mean that the wealthy will cease practicing, because wealth, historically, was not associated with irreligiosity.