How Far Things Have Fallen in the Netherlands

The Dutch are among the least religious today, but it wasn't long ago that they were among the most devout.

The Dutch are known for their irreligiosity. In the seventh wave of the World Values Survey conducted in 2022, only 8% attended church weekly (61% reported that they never attend). Only 31% said they believed in God. Only 26% adhered to a Christian denomination.

I highlight this to draw the contrast between the atheistic Dutch of the twenty-first century and the Dutch of the mid-twentieth century. Things were not always this bad. In fact, the Dutch used to be among the most religiously devout well into the middle of the twentieth century.

A photo I found from Alamy of St. Bravo Cathedral in Haarlem in the 1950s, seemingly well-attended.

For instance, at mid century, the Dutch were as faithful in their church attendance as Americans. A nationwide survey conducted in 19561 revealed that 46% of the Dutch public attended church regularly. That same year in the United States, at the high point in its history for church attendance, 49% reported attending regularly.

Those aggregate church attendance figures obscure other remarkable facts. Among Catholics in that 1956 survey, 87% attended regularly. Those belonging to the more conservative of the two major Protestant denominations, the Reformed Churches in the Netherlands, had similarly high levels of church attendance, with 84% attending regularly. Although it lagged far behind Catholics and orthodox Calvinists, even a third of the liberal Dutch Reformed Church attended regularly.

It may be tempting to dismiss such levels of church attendance as merely the consequence of ignoring those who had been raised in the faith and walked away. Church attendance may seem like it was high, but if large shares of those raised in the faith walk away in adulthood, then what seem like high levels of church attendance may actually be quite low once all those raised in the faith but who left are taken into account.

Such skepticism, however, is unwarranted. A survey conducted a decade later reported similar levels of Mass attendance among Catholics, with 85% reporting that they attended regularly. That 85%, however, was not due to the pyrrhic health of the Dutch Church at mid century masking a sea of baptized Catholics who had left the church, for 85% of those raised Catholic remained so in 1966.2 Including those who left the faith in the denominator puts regular attendance at 76% among all those raised Catholic—in turn, putting to rest the idea that the high rates of church attendance were inflated. Comparing the Dutch once again to Americans, 75% of American Catholics attended regularly.

The one denomination where the faith inculcated in childhood failed to carry on into adulthood was with the Dutch Reformed Church, where less than half (49%) of those raised Dutch Reformed remained so in adulthood. Few (less than 3%) of those who left the church did so for the more stridently Calvinist Reformed Church in the Netherlands. The more orthodox of the two major Protestant denominations had rates of retention of its adherents similar to those of Catholics. The fact that the more liberal Dutch Reformed Church had substantially lower levels of retention of adherents is in line with arguments made by those like Steve Bruce that liberal religion undermines both the rationale for those raised in the church to stick with it and the impetus (as well as the content) for parents to instill it.3

What’s also interesting about the vitality of church attendance in this period is how little attendance varied by age. Take Catholics for instance: using that survey from 1956 and breaking respondents down by age shows that younger respondents were at least as likely as older respondents to attend regularly. In fact, the youngest cohort, those aged 18-25, were the most likely to report attending regularly.

Since the 1960s, secularization has been blamed on young people turning away from the Church, then failing to pass along any lackluster residual faith they might have to their offspring, and so on. This paints a picture of church attendance merely falling out of fashion with the new generation. If that were true, we would expect to see some signs of that generational wave in the years leading up to the secularization of the 1960s.

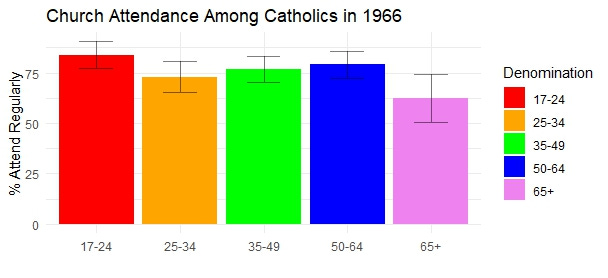

As it turns out, however, we fail to see this pattern play out even in the 1966 survey—the one conducted as the trend towards secularization had begun. Looking at regular church attendance among all respondents who were raised Catholic, we see that roughly similar percentages of those aged 17-64 attended regularly (again, though, the youngest cohort appears to attend the most, not the least, often). The only group that stands out are those aged 65 and up, who have by far the lowest levels of attendance. Remarkably, this finding holds up for both Calvinists and Dutch Reformed respondents as well.

Looking at these data from 60-70 years ago is helpful for two chief reasons. For one, they contradict the received wisdom regarding the genesis of declining church attendance. If anything, the fact that these percentages are taken from among all those raised Catholic means that if one were to have looked at these figures at the time these surveys were collected, one would be left with the conclusion that the future looked bright for Christianity in the Netherlands, especially Catholics and orthodox Calvinists.

On this last point, the second reason looking at these data is helpful is because they remind us how quickly things can change—and how quickly they have changed. Not only does this offer an important lesson on how perspective can be altered (as noted above, forecasting the future from the standpoint of 1966 yielded a far different prediction than the ones we might arrive at in 2025), but it reminds us how different things were not that long ago. Could this radical reversal of fortune work in the opposite direction? While it’s not likely, the radical change seen since the data examined here were gathered reminds us not to rule it out.

Namely, I use the “Common ideas about foreign countries” survey conducted in 1956.

The data from 1966 come from the “God in the Netherlands” survey.

Steve Bruce, Choice and Religion: A Critique of Rational Choice Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999, chapters 6 and 7.