Liberals on the Right

Not all "conservatives" value the conservation of religion, and it shows.

In writing about theology and its impact on religious devotion, I try to steer clear of the term “conservative.” So much hangs on the definition of that word. Especially when we enter into discussions regarding the intersection of politics and religion, the definition of political conservatism muddies the waters. This obscures the impact of both liberalism and conservatism on religiosity.

For that reason, I try to avoid talking about theological “conservatives” when talking about the antithesis to theological liberalism. Instead, I prefer the more precise term reflecting what I intend, “orthodox.” But there are times when we need to talk about conservatives and religion. In this case, I am talking about the impact of “conservatism” on the religiosity of its devotees.

The problem with conservative politics is that what is often labeled as conservative is actually a defense of pure, unadulterated liberalism. This is particularly the case in the United States, where the conservative movement has long sought to preserve and spread philosophical liberalism, particularly the eighteenth-century liberalism that gave rise to the Declaration of Independence, the Bill of Rights, and the free market. However beneficial these developments may have been, the liberalism behind them often stands in tension with philosophical conservatism and the institutions and values that conservatism seeks to secure.1

In some European countries today (and in earlier eras for others), such institutions include the monarchy, the nobility, the land (particularly as it relates to the maintenance of agriculture, a key source of the nobility’s power), and class divisions that promoted harmonious order. Beyond these, conservatives have been concerned with more eternal institutions like the family and the Church. Whereas liberalism seeks to liberate the individual from the constraints imposed by these (and other) institutions and the bonds of duty they impose on the individual, conservatives seek to preserve the rights and privileges conferred to these institutions because they are viewed as beneficial to the wider community (to which the individual belongs).

While there is a tendency within conservatism to update the list of institutions and values that should be conserved as circumstances change, which has since the emergence of socialist parties included defense of individual liberties and the free market, conservatives differ from liberals in that they recognize the tension, for instance, between defense of individual rights and protection of the Church (a communal organization that places many normative limits on individual action). Recognizing such trade-offs and seeing that defending an institution like the Church may be more important to society than protecting an unfettered free market (the values of which may conflict with and undermine the position of the Church), conservatives seek to conserve the Church and its interests while liberals hold the free market in higher regard.

Accordingly, the labels that are applied to these philosophies become confused. While it is true that many parties and politicians on the right today wish to conserve values like individualism and institutions like the free market, not all (perhaps very few) should be defined philosophically as conservatives. If the values and institutions of liberalism are held in highest regard and their defense is viewed as the primary political objective, then those holding such views should be properly understood as liberals—perhaps as conservative liberals, reflecting the fact that they seek to conserve liberalism at all costs.

Part of the difficulty with distinguishing conservatism from liberalism is that the two ideologies have often been grouped together by politicians on the right. Since the Liberal Party in the United Kingdom started drifting further to the left as the classical liberalism of the Whigs (think pure laissez faire) began to be displaced by social liberalism (using ever more state power to defend individual rights that cannot be secured through the market) as the party’s animating philosophy, conservative liberals have sided with the Conservative Party. This process of realignment accelerated after the Labour Party displaced the Liberals as the largest party on the left. While the Conservatives managed to maintain a balance between tory conservatives (those holding eternal goods in highest esteem rather than the free market) and conservative liberals for decades—offering a defense of traditional institutions like the monarchy to the former and a defense of the free market to the latter—the balance of power in the party shifted drastically in the liberals’ favor following the ascendance of Margaret Thatcher to the leadership of the Conservative Party. Since the mid-1970s, tory conservatives have played a marginal role in directing the Conservative Party while the party in Parliament has focused on providing a conservative defense of liberalism—even at the expense of the Church (of England).2 The dominance of conservative liberals has been even more pronounced in other right-of-center parties in the Anglosphere, such as the Liberals in Australia and the Conservative Party of Canada (especially the wing of the party from Western Canada). Even many of Europe’s conservative parties have become more liberal and considerably less conservative. This can be seen, for instance, with the free-market turn of Sweden’s Moderate Party (formerly known as the Conservative Party) since the late 1970s.

Reuters didn’t exactly pen the type of eulogy a “Conservative” would have, but their write-up summarizes the liberal impact her premiership had—which Conservatives continue to reverently demand from their leadership like the laity expects of a liturgy.

The distinction between conservatism and liberalism is important because not all conservatives are philosophically insulated from secularization. While philosophical conservatives (or at least those with a conservative disposition) may defend the interests of religion (and other traditional institutions) as the highest order, the values held by liberals make them susceptible to anti-clerical impulses that seek to subvert religion. When push comes to shove, many conservative liberals may actually favor secularization over religion, especially when religion infringes on individual liberties or interferes in the market. Think, for instance, about the repeal of Sunday trading restrictions: although it undermined the church and reduced the religiosity of the population,3 lifting these restrictions freed the market and was good for business.

The affinity between liberalism and secularization can be seen by looking at the religious views of prominent conservative liberals. The chief proponents of post-War neoliberalism in the United States and elsewhere, Milton Friedman and F. A. Hayek, were both irreligious. Many of the most prominent libertarian writers do little to hide their contempt for religion (one need only browse through the pages of Reason Magazine for apt examples), but even “conservative” commentators like George Will and Bret Stephens make their antipathy towards religion known from time to time, especially when social issues of concern to religiously devout voters are raised. Even the doyen of the conservative movement in the U.S., Barry Goldwater, embodied the secular impulses of liberalism: not only was he personally uninterested in his mother’s Episcopalianism, but he thought little of religious conservatives, and in keeping with his liberal views, often supported policies opposed by religious conservatives that “liberated” the individual (e.g., abortion and drug legalization).

Although liberals express varying degrees of anti-clericalism, the common theme is that liberalism and religion exist in tension with one another. This implies that elevating liberalism as the chief concern in politics will make religious concerns subservient to the promotion of liberalism (if they are considered at all). When religion and liberalism collide, liberalism will crowd out religion. Although those on the left (including those on the “left” within a conservative party) will be the most likely to secularize, those most committed to liberalism will be more likely to disengage and disaffiliate from religion than conservatives who may value the free market but view the interests of religion as having primacy.

We can see the replacement of religion with faith in liberalism illustrated particularly well in Britain at the end of the twentieth century. From 1974 until at least the late ‘90s (though arguably later than that), the Conservative Party in Britain became a party that put its faith in the free market. Under the leadership of Margaret Thatcher, the party began to shift away from the paternalistic managerialism that characterized the party since the 1930s, replacing this posture with one fully ensconced in neoliberalism. Thatcher and her circle drew inspiration from the works of those like F. A. Hayek and Milton Friedman, who sought to shrink the administrative bureaucracy that had accumulated over the decades by deregulating the economy and privatizing the state-owned firms as a means to steer Britain out of the slow-growth, high-inflation economic trap that characterized the 1970s.

The Thatcherite wing of the party wrestled control of the party with her election as leader of the Conservative Party in 1974 from an establishment that had grown tired and lost confidence in itself. From a lower middle-class background herself, Thatcher was a rousing figure for many Conservatives (and not a few Britons outside the Conservatives’ traditional base of supporters) who drew inspiration from the fact that her rise to power from humble beginnings through self-determination and hard work represented the triumph of (liberal) British values. The fact that Thatcher’s patriotic spirit harkened back to an earlier liberalism that she promised to restore once the Conservatives were elected in 1979 reinvigorated the spirits of party members and re-energized conservatism more broadly. (It will be remembered that Thatcher embodied what many Americans view as Reaganism before Reagan came to power in his own party, let alone before he was elected president.) Whilst other British institutions—such as those of the British establishment, including even the Church of England—lost their luster in the malaise that permeated the 1970s, Thatcherism offered Conservatives a competing ideology in which to place their hopes. This was a faith in the free market, which if only it could be released from the cage in which it had been imprisoned since the modern administrative state had formed, Britain could restore herself to the glories she had known in earlier times when the philosophy governing the country was laissez-faire liberalism.

The only problem with Thatcher’s liberalism was that it sometimes came at the price of conservatism. Thatcher’s government was so focused on cleaning up deadweight dragging down the economy through deregulation that other conservative principles were undermined in the process. Although her team included many from the British establishment, the liberalism to which each was devoted was anti-establishment. Tightening budgets and deregulating archaic economic practices sometimes produced collateral damage not only to the British establishment Conservatives had previously cherished,4 but also for the role of religion in society. It was, after all, the Conservatives who pushed and eventually succeeded in expanding Sunday trading: in seeking to free the market, many Conservatives forgot God’s commandment to keep the Sabbath holy. Few Thatcherite Conservatives had much time or concern for other social questions, including questions of moral traditionalism that, whilst not the top priority of the average Conservative voter, nonetheless remained important for many Conservatives outside Thatcher’s inner circle. This is evinced by the fact that on specific questions like abortion, more general questions pertaining to the Sexual Revolution, and even the place of the Church in British society, the Conservative governments of the 1980s and ‘90s ceded ground without much of a fight.

Taken to its logical conclusion, the liberalism that characterized the Conservative Party during the Thatcher years sought to reduce everything to questions of material cost and benefit. This faith in liberalism stood at odds with the teachings of the Church of England (which was still a Christian institution in those years). Although members of the party could have continued to place their faith in the same religion provided by the same institutions that their forefathers had turned to in the centuries before them, savvy Conservatives recognizing the broader social trends pointing to a diminished role for religious institutions might more easily turn to the new religion offered by the Thatcherite wing of the party. Rather than placing faith in God and the institutions of the Church, which only were a drag on economic activity anyway, Conservatives could instead pledge their faith to the god of the market and hope for all the (material) blessings that free enterprise could deliver.

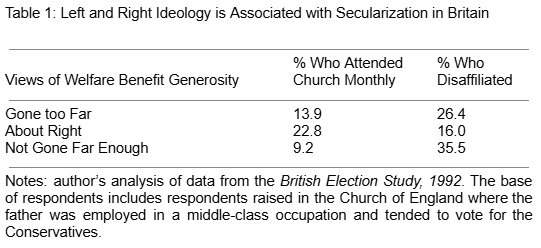

Table 1 illustrates these points using data from the British Election Study conducted following the conclusion of the 1992 general election—the first election after Mrs. Thatcher’s ouster in 1990, but still during a time in which her economic and political philosophy reigned (her successor, John Major, led the Conservatives to an upset victory in 1992). Specifically, Table 1 presents responses to a question touching an issue that went to the core of Thatcherism: the generosity of the welfare state. Respondents were queried about “The welfare benefits that are available to people today,” with response options ranging from saying that the generosity of welfare benefits had gone (much) too far or not gone (nearly) far enough (with “about right” in the middle of this scale). Those who felt that welfare benefits remained too generous after 13 years of welfare retrenchment by that point represented the true believers in Thatcherism, that Thatcher’s government had not liberated the economy enough. Those who felt that welfare generosity at that time was about right reflected the views of solid Conservatives who approved of the cuts to welfare benefits to that point but were not as zealous in their desire to reshape Britain’s economy as the true believers—while those who thought that the levels of welfare benefits had not gone far enough represent the One-Nation Conservatives who have since the era of Benjamin Disraeli tended to be more favorable to state intervention in the economy to provide for social stability.

The responses are restricted to those who were most likely to face the temptation to replace their religion with Thatcherism. Namely, the data in Table 1 include those who were raised in a middle-class family who identified with the Conservative Party. These are the people socialized in the Conservative Party who are its core base of supporters. Moreover, the figures in Table 1 only include such respondents if they were raised in the Church of England. The Church of England has long been referred to as “the Conservative Party at prayer” due to the close affinity between the two institutions, what with the Conservatives’ historical support for the institutions of the British establishment like the Church of England (to which the monarch must belong as the supreme governor of the state religion). Yet it is these dyed-in-the-wool Conservatives who faced tensions between their faith embodied in the Church of England and the faith which the Thatcherism that governed the Conservative Party placed in the market. If liberal politics on the right can displace religion, then it should be those most fervent in their crusade to return to Hayekian economics and reduce the generosity of the welfare state who are less religious than Conservatives who went along with privatization and deregulation but who were not as deeply devoted to that cause at all costs.

As it turns out, among this group of people socialized in an environment favorable to the Conservative Party, the extent of secularization is greater among those holding the most ardently liberal (i.e., Thatcherite Conservative) positions on the welfare state than those Conservatives with more moderate views. Whereas 22.8 percent of those who felt that the generosity of welfare benefits was about right attended church at least once per month, only 13.9 percent of those felt that welfare benefits remained too generous attended monthly.

In case one distrusts this measure of religiosity, the same pattern emerges when looking at the share of each group that quit the Church of England. While more than a quarter of those who held the Thatcherite position that welfare benefits remained too generous had left the Church of England by 1992, only 16 percent of those who felt that the level of welfare benefits was about right had disaffiliated. This provides evidence that some of those who held the Thatcherite faith in free-market economics had replaced their faith in God.

While liberal and libertarian thinkers have had profound influence on Republican Party policy and conversations among thought leaders on the broader political right, their impact on the grassroots has been far more marginal than is the case in Britain. This is because church leaders also remain important in shaping the thinking of American conservatives—unlike with most British conservatives, who as members of the Church of England, rarely attend church to interact with their priest. Pastors are much more concerned with matters regarding how faith should be integrated into politics than is the average policy scholar at the Cato Institute, and are much more relevant in the lives of the average Republican voter than the average Conservative in Britain. As a result, the average Republican voter is much less concerned with free trade and marginal tax rates than the average elected Republican, and instead much more concerned with abortion and which bathroom people are allowed to use. Because the average Republican still has a faith to believe in, and because this is more often than not a faith that clings to orthodox Christian views, Republicans have been secularized far less by liberal individualism than has been the case in Britain.

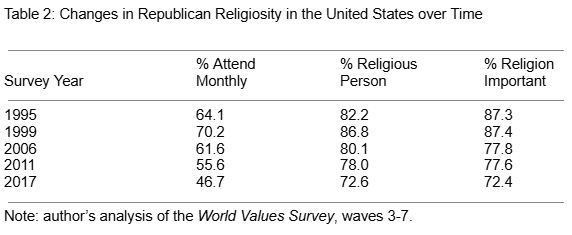

Still, considerable secularization has resulted from conservative liberalism. Using data from the World Values Surveys, Table 2 displays levels of religiosity using three indicators: the percentage attending church services at least monthly, the percentage identifying with the term “religious” (versus “not a religious person” or “atheist”), and the percentage saying that religion is important or very important in their lives, broken down by party preferences.5 Whereas monthly attendance among Republicans was around 70 percent at the turn of the millennium, less than half of Republicans attended monthly or more in 2017. While the overwhelming majority of Republicans still describes themselves as “religious,” the percentage doing so has dropped from just under 87 percent in 1999 to less than 73 percent in 2017. Nearly identical is the drop in the percentage saying that religion is important in their lives.

Beyond showing that secularization has penetrated the Republican Party, the timing of secularization in the Republican ranks seen in Table 2 points to an interesting reason. On each measure, religiosity appears healthy among Republicans during the 1990s. The downward trajectory of religiosity for the average Republican becomes apparent in 2011, continuing through 2017. In addition to attracting more support from ideological conservatives as the public began to sort itself more neatly into the two parties, one will remember that the Republicans of the 1990s were the party of the Christian Coalition, Culture Wars, and the crusade against the Clintons’ ethics and morals. During the administration of George W. Bush, however, the party shifted more in the direction of Charles and David Koch, the libertarian philanthropists who were much more interested in promoting free trade with China than the concerns of Culture War conservative Christians (neither brother has expressed much interest in religion). Given that the most “conservative” Americans were more likely to disaffiliate and disengage than those somewhat less conservative during a period in which conservative has come to mean libertarian, it is unlikely a coincidence that religion has faded in importance among Republicans. As the party has tried to move past Culture War issues to focus on a full-throated defense of the free market and liberal individualism, the Republicans may have undermined a good that conservatives (rightly understood) would have been more concerned about: religion.

Although some ministers and Christian commentators have sought to marry Christianity with conservative liberalism,6 they may have forgotten that one cannot serve both God and money (or even the market).7 Either one will put the Church and her interests first, or the market. In putting their faith in liberalism and placing the market above all else in politics, “conservatives” may have led themselves down a path to secularization.

Readers interested in a longer, fuller discussion of the tensions between liberalism and conservatism on the right should consult Yoram Hazony’s work: Conservatism: A Rediscovery. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2022.

See, for instance, the discussion of these tensions in Andrew Gamble, The Free Economy and the Strong State: The Politics of Thatcherism, 2nd Edition. Houndmills: Palgrave, 1994.

The effects I speak of can be seen in Gruber, Jonathan, and Daniel M. Hungerman. “The church versus the mall: What happens when religion faces increased secular competition?” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 123, no. 2 (2008): 831-862.

In trying to use the power of the state to reorder society according to its liberal vision, the Conservatives bypassed other institutions like the Church and other civil society organizations. In doing so, they further degraded the already waning authority these institutions still commanded, in turn undermining the foundations upon which the liberalism they sought to cultivate had flourished in earlier eras: see Andrew Gamble. The free economy and the strong state: The politics of Thatcherism. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 1994.

“Party” here refers to the party respondents would vote for in a hypothetical election held at the time of interview. While this is not a perfect measure of partisanship, for intended voting behavior is more volatile than party identification, it nonetheless provides an indicator of party preferences.

Consider a few examples. Pastors Bryan Fischer and Johnnie Moore typify examples of ministers that have sought to merge Christianity and economic liberalism. See Bryan Fischer. “No, Jesus Was Not a Socialist,” The Stand, May 17, 2016, available at: https://afa.net/the-stand/faith/2016/05/no-jesus-was-not-a-socialist/; Johnnie Moore, “Was Jesus a Socialist or a Capitalist?” Fox News Radio, October 5, 2016, available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20161005230518/http://radio.foxnews.com/toddstarnes/top-stories/was-jesus-a-socialist-or-a-capitalist.html. Among laypeople, Jay W. Richards of the Discovery Institute, who holds a Master’s of Divinity degree, and Lawrence Reed, of the Foundation for Economic Education, have claimed that Jesus was a capitalist: see Tyler O’Neil. “Was Jesus a Capitalist? Christian Scholar Argues for Free Market, New Understanding of Financial Crisis,” The Christian Post, August 18, 2013, available at: https://www.christianpost.com/news/was-jesus-a-capitalist-christian-scholar-argues-for-free-market-new-understanding-of-financial-crisis.html; Reed, Lawrence (2015). Rendering unto Caesar: Was Jesus a Socialist? Atlanta, Georgia: Foundation for Economic Education.

As Christians will recall from Matthew 6:24 (NIV), “No one can serve two masters. Either you will hate the one and love the other, or you will be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve both God and money.”