Orthodoxy Matters; Just Look at the Orthodox

Comparing one branch of Orthodoxy known for its doctrinal conservatism with another known for being less so highlights the importance of orthodoxy

It’s easy to overcomplicate matters when analyzing big, contested topics. Drilling into ever more minute details seems like a surefire way to uncover unassailable truths that prove our arguments right against any hope of challenge. Almost always, however, the complicated logical trail needed to connect the rabbit holes we dig ourselves into are so tenuous that we often risk losing sight of the point we intended to make and ignore simpler means of demonstrating our point.

A case in point for me regards my contention that liberal theology undermines religion. I’m always on the hunt for that example which favors my argument yet stacks the deck against my claim being true—and most favorable to all the competing claims I have to contend against; such evidence is always the most convincing. That means lots of nuance, complication, and detail—and very little to show for all that effort.

And yet a simpler example I had toyed with long ago came to mind: examining differences in observance among Orthodox Christians. The particular survey was The Orthodox Church Today study, which was a survey of American Orthodox parish members conducted between 2006 and 2007. The survey focused on members belonging to the two largest Orthodox groupings, the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese in America and the Orthodox Church in America. Because Orthodoxy is generally known for, well, its theological orthodoxy, and because the Orthodox Church in America is more well-known for its comparative doctrinal strictness, then this means that differences in religious practice observed between the average member of these two groups would provide fairly clear evidence of the importance of orthodoxy for sustaining religiosity.

The two hierarchs literally came face to face.

First, regarding the claim that members of the Orthodox Church in America (OCA) are stricter, doctrinally speaking, in their Orthodox orthodoxy: although members of the OCA and the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese in America (GOAA) were equally likely in the survey to describe themselves as doctrinally conservative or traditional, members of the OCA were less likely to describe their parish as “modern.” When comparing theirs to the “typical” Greek Orthodox parish, 26% of members of the GOAA said that “We are more ‘modern’ and allow for more differences of opinion in application of Orthodox principles to everyday parish life” while only 17% of members of the OCA gave this response. Members of the OCA were also more confident in the truth of Orthodoxy, with 59% strongly agreeing that “Orthodox Christianity contains a greater share of truth than other religions do”—compared to 49% of members of the GOAA. At a higher level, most of the scandalous actions in defiance of their titles as “orthodox” Christians taken by American Archbishops in the past few years have been found in the GOAA.

Now, regarding our ultimate concern of observing differences in religious practice, these differences in orthodoxy and theological certainty, however slight, correspond to measurable differences in religious observance. While both groups’ members reported high rates of weekly (or more) attendance due to the nature of the design—parishes were instructed to distribute the survey to active members—rates of weekly-plus attendance were higher among OCA members (95%) than members of the GOAA (83%). It is a simple test, but one which serves to vindicate the thesis that liberal theology undermines religion.1

Not only do we find validation of our thesis when looking between different the two denominations, but we find further confirmation of the argument when looking at members in both denominations. While more than two thirds of members of both denominations described themselves as conservative or traditional, our thesis leads us to predict that those who described their theological views as moderate (just over a quarter of members in both denominations), and certainly those who describe themselves as liberal (4% in both), should be less likely to attend weekly than conservatives and traditionalists.

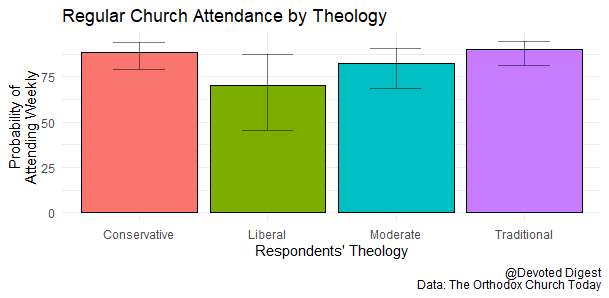

Even after controlling for differences in age, education, sex, parents’ religiosity, how modern or traditional respondents’ parents were, the ethnic makeup of the parish, and whether respondents were cradle or convert, we see that theological liberals are significantly less likely to attend weekly than theological conservatives and traditionalists. Assuming a male respondent who was a cradle member of the GOAA whose parents were active members, the probability of attending weekly for traditionalists is 90%, 88% for theological conservatives, 82% for moderates, and only 71% for liberals. Stated simply, this provides further proof that theological liberalism undermines religious devotion.

I doubt this will be the last time I examine this topic (actually, I can guarantee it). But clear-cut examples like this are particularly helpful in demonstrate a point simply and effectively. And that point is that liberal theology is detrimental to faith.

These differences hold even after controlling for a host of other factors (mentioned in the text above when discussing the impact of respondents’ own theology on their probability of attending regularly) using a logistic regression model.