Secularization Before Economic Development: The Case of Sweden

Contrary to the claims of many secularization theorists, the experience of Sweden undermines the claim that economic development causes religion to fall.

There is no case presented more frequently as a vision for what a post-Christian future will look like than Sweden. Sweden shows up often in scholarly treatments as a useful illustration of the impact of economic development and material comfort on secularization.1 There are even book-length treatments examining Sweden’s post-religious society and culture as a glimpse of the future the rest of the world can expect to follow.2

Sweden is held up as an example because its economy looks like the model Secularization Theory says will enervate religiosity. Not only is Sweden an advanced industrial economy that has delivered prosperity, but its material benefits have been distributed widely, with one of the most equal societies in the world—with such material equality supported by a generous welfare state. The fact that few go hungry in Sweden means that the psychic benefits of material comfort are enjoyed nearly universally in Sweden—which if Secularization Theory is right, implies that people are less religious because they have little need for religion to cope with the misery of life if life there is so great.

It is correct to say that, today, Sweden represents a case in which high levels of economic development and material security on the one hand are paired with low levels of religious participation and belief on the other. To argue that the low levels of religiosity seen in Sweden are a downstream consequence of societal changes rooted in economic development, however, demonstrates that one does not have their facts straight. If anything, doing so risks telling the story backwards.

Sweden hasn’t always been the wealthy society we know of today. Not too long after this illustration was created, the earliest church attendance figures showed that the country wasn’t very religious either.

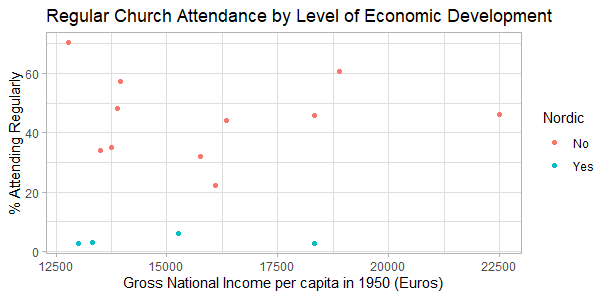

When authors evaluating the state of secularization in post-War Europe and projecting further declines of religiosity into the future looked at a case like Sweden, they saw much the same association between economic prosperity and religious disengagement that we see in Europe today. The figure below shows that when we look at the association between countries’ levels of weekly church attendance3 and economic development in the 1950s,4 there is a negative, albeit weak, correlation between these two measures. Looking at such a correlation at this one point in time would lead one to the conclusion that wealthy countries like Sweden—and the other Nordic countries: Norway, Denmark, and Finland—had such low levels of church attendance and religiosity because they were so wealthy. When looking at such a correlation, one could be forgiven for assuming that Sweden was an early industrializing nation that experienced the material benefits of industrialization earlier than other countries, and for that reason also experienced lower levels of religiosity early as well.

Although data pertaining to religion dating back prior to the nineteenth century are harder to come by than the mass social survey that became the standard tool of social scientists following the Second World War, Sweden is a rare case. The sociologist of religion Steve Bruce did the field a great service in collecting rates of weekly church attendance reported in previous research for several countries, Sweden included, dating back to the nineteenth century. While the other Nordic countries had similarly low levels of weekly church attendance in the early twentieth century, Bruce had one data point from 1890 for Sweden showing that only 17 percent of Swedish Lutherans (constituting more than 95 percent of the population) attended weekly—a level of church attendance that puts nineteenth-century Sweden on par with many European countries in the late twentieth century. By 1927, attendance had already dropped further to 5.6 percent, declining further still to 2.9 percent into the 1950s where it has remained ever since.5 This shows that Swedes have long been a non-practicing people.

Because economic data dating back to the nineteenth century are easier to come by, we are able to tell that Swedes have been religiously lax longer than they have been prosperous. Industrialization in Sweden began in the 1870s, but not to the degree seen in early industrializers like the United Kingdom until the turn of the twentieth century.6 When industrialization, and especially the material benefits of industrialization, did finally take off, the figures reported in Bruce’s research noted above show that Swedes were already quite lax in their religious participation. This makes it hard to sustain the claim that it was industrialization that led to the changes in society that undermined religious belief and practice.

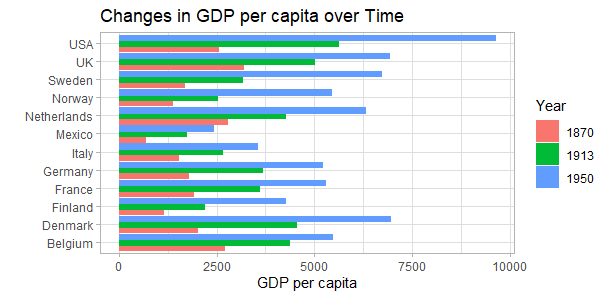

Moreover, the material benefits of industrialization in Sweden were not to be felt in full until well after religious practice had already declined to the low levels seen above. Until well into the twentieth century, the figure below shows that Sweden was considerably poorer than most of Europe. While Sweden was among the wealthiest countries after the Second World War, it was among the poorer countries in Western Europe at the turn of the twentieth century. This shows that when most Swedes were not attending church services in the late nineteenth century, they were not living in the material abundance that Swedes have enjoyed since the middle of the twentieth century. Because the nonreligious Swedes were poorer than many other nations in Western Europe that had much higher rates of church attendance, this undermines the claim that Swedes are irreligious because they are wealthy. Most Swedes are not religiously devout, but their levels of material comfort have little to do with this fact.

The Swedes were not alone, on either account. As noted above, the earliest levels of church attendance witnessed in the other Nordic countries were also quite low—less than 10 percent from the earliest sources and less than 5 percent by the 1950s.7 Not only that, but the other Nordic countries were also comparative laggards in terms of their economic development. Like Sweden, the figure above shows that Denmark, Finland, and Norway all had low levels of economic prosperity, too. This means that the key countries used by those working in the Secularization Paradigm to demonstrate the negative association between economic development and religiosity have got this relationship wrong. Contrary to what Secularization Theory tells us, religion declined first not in the most developed of Western economies, but instead some of the least.

Inglehart, Ronald. Religion's Sudden Decline: What’s Causing It, and What Comes Next? Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021.

Zuckerman, Phil. Society without God: What the Least Religious Nations Can Tell Us about Contentment. New York: NYU Press, 2008.

1950s attendance rates were taken from several sources. In addition to the data from Steve Bruce (see Note 5 below) for the Nordic countries, as well as Australia, data for the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, and Mexico were taken from the Almond and Verba Civic Culture study. Data from the Netherlands and Belgium were taken from a similar instrument fielded in both countries in 1956; data for France were taken from Mattei Dogan’s chapter in Lipset and Rokkan’s edited volume from 1967, Party Systems and Voter Alignments (New York: Free Press). Canadian data were from a 1956 survey fielded by Gallup’s Canadian operation.

Figure 1 uses gross national product per capita using data collected by Paul Bairoch. See Bairoch, Paul. “Europe's Gross National Product: 1800–1975.” Journal of European Economic History, 5, No. 2 (1976): 273–340. The conclusions reached here are reinforced by using an alternative measure of gross domestic product per capita produced by Angus Maddison. See Maddison, Angus. “Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD. Essays in Macro-Economic History.” Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 379, table A.4.

Bruce, Steve. Choice and Religion: A Critique of Rational Choice Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, USA, 1999, pp.209-226, though for the specific figure for Sweden in 1890, see p.217.

Jörberg, Lennart. “Structural Change And Economic Growth: Sweden In The 19th Century.” Economy and History 8, no. 1 (1965): 3-46; Schön, Lennart. “Sweden–Economic Growth and Structural Change, 1800-2000.” EH. net Encyclopedia (2007); Prado, Svante, and Jakob Molinder. “Modern Swedish Economic History.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia Of Economics And Finance. 2022, available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190625979.013.679.

Bruce, 1999, p.217.